In an interview with George Scoville of On the Forecheck, Anne Marie Clune comments on how Ted Reeve Skating Hockey School helped their family growing up in Toronto.

“I didn’t know anything about hockey, I just knew my kids wanted to play,” said Anne Marie Clune in a recent phone interview. Anne Marie is mother to Nashville Predators left wing Rich Clune and Ontario Reign (ECHL) defenseman Matt Clune.

Anne Marie’s husband, Tom Clune, grew up playing hockey himself, the only one of seven children in his family to play competitive sports. With roots in Canadian youth hockey, and after playing for Colby College in Maine, Tom would eventually travel to Sweden, where he played in a semi-professional league. The decision to put Rich, Matt, and Ben into hockey school rested mostly with him, says Anne Marie.

The Clunes grew up playing House League hockey at Ted Reeve Arena, a community rink erected in 1954 with help from both the City of Toronto and the voluntary contributions of various benefactors:

In the very late 1940’s, a group of East End Toronto residents felt an indoor hockey arena was needed and set out to raise half of the money required, with the City of Toronto contributing the other half. Door to door fundraising took place and Ted Reeve, a Toronto Telegram sports writer, and a professional level athlete, wrote some articles to assist the effort to build the rink.

The doors opened October 1954. An arena built by the community, for the community and that is how it is still operated today, as Ted Reeve Community Arena.

“Where we live is an interesting, old, ethnically diverse part of Toronto,” said Anne Marie. “There is a mix of incomes in our area.”

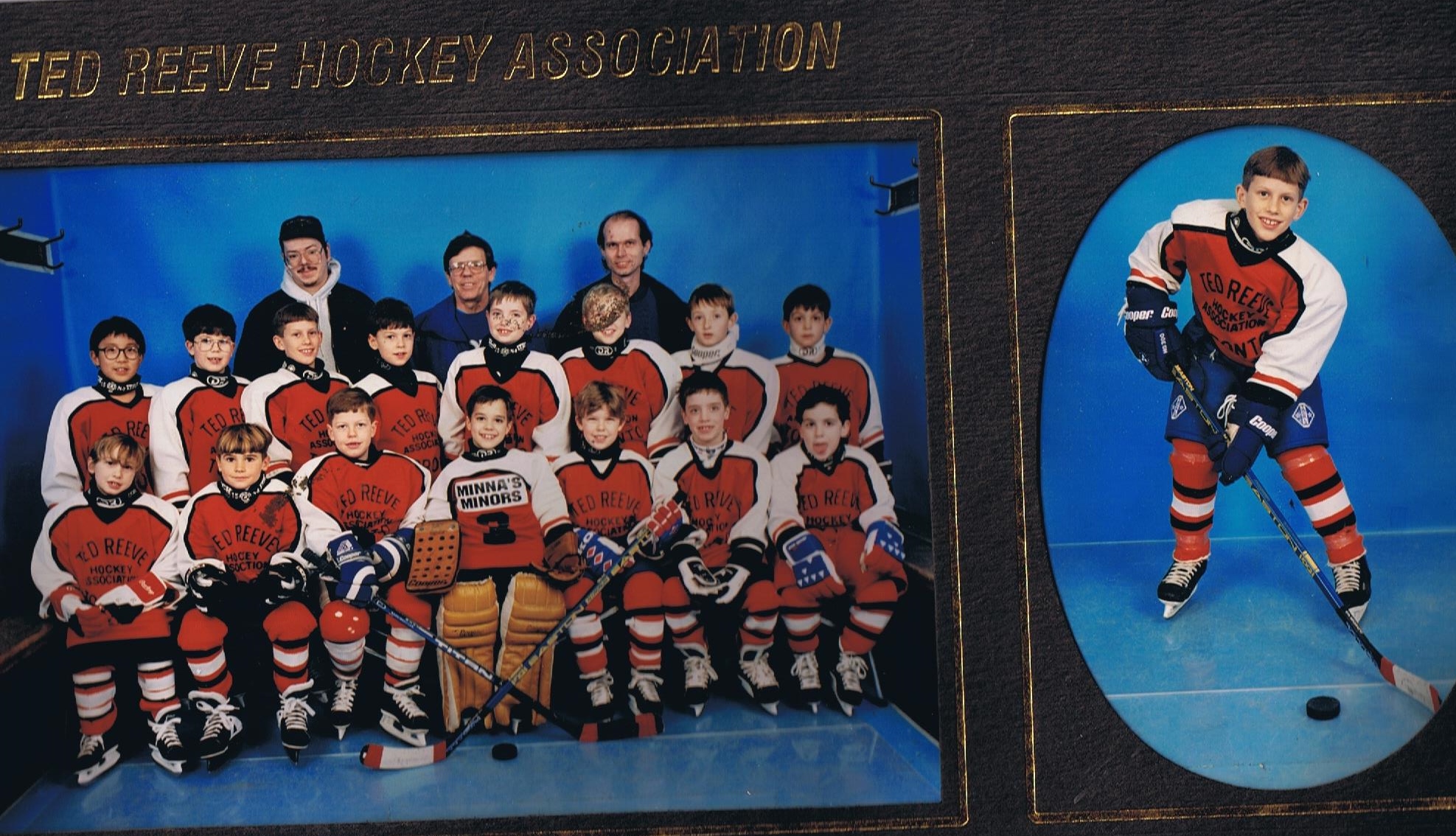

The Ted Reeve Arena Skating and Hockey School, where the Clune brothers began their paths to professional hockey, has enjoyed tremendous staying power, and has drawn continuous support from the very community it serves.

“I am pleased to report we are in our 44th year at the School,” wrote Paul Casey, current treasurer and secretary of the Ted Reeve School, in an email. “All of our Board members and instructors,” of which Casey is also one, “are volunteers,” he said. “All of our volunteers are very proud of our School and the role we play in the community.”

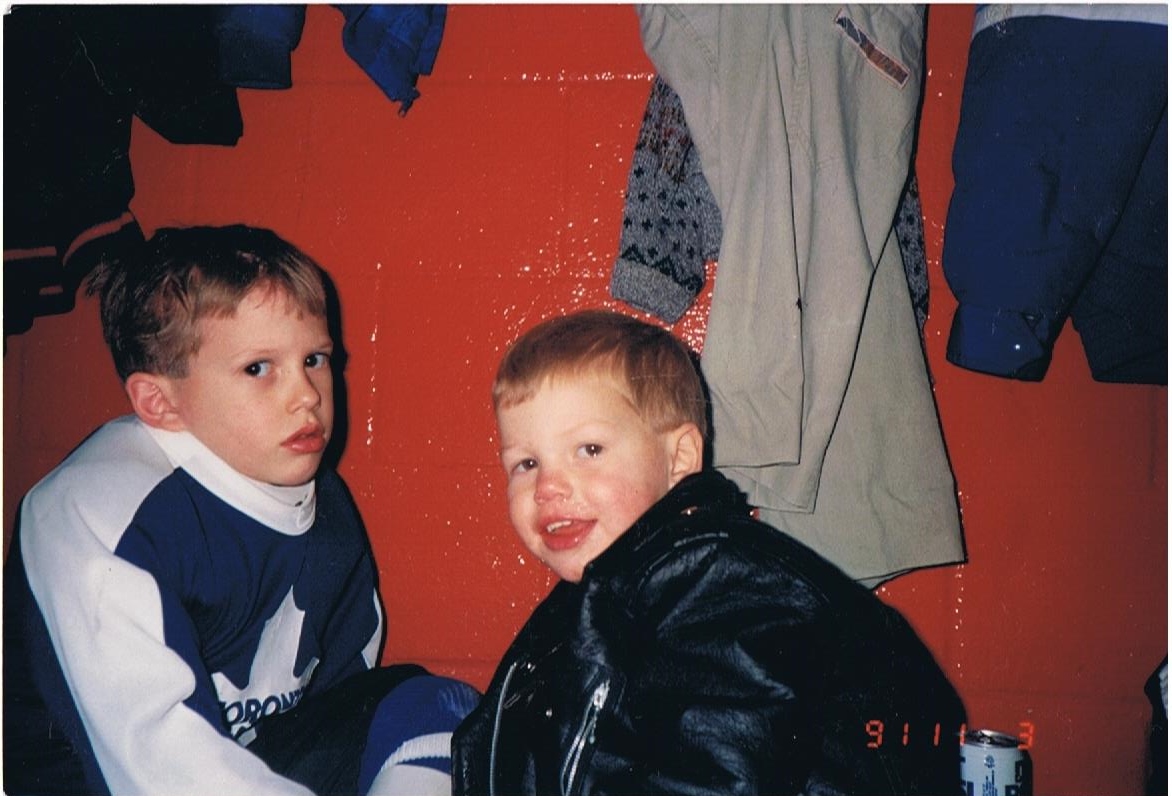

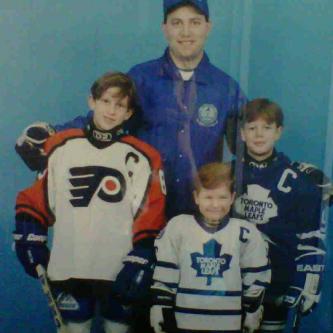

(Left to right): Matt Clune, Ben Clune, and Predators’ ‘working man’ Rich Clune as children, pictured with their father Coach Tom Clune, at Ted Reeve Skating Hockey School.

Tom Clune, pictured above, was a volunteer instructor at the School when his sons were younger. He taught 7-14 year olds how to skate for four hours every Sunday afternoon. “He was very old school,” said Anne Marie. “Put a chair on the ice, and get the kids to push it, that’s how ‘Coach Clune’ taught skating.”

Aside from the man hours its volunteers dedicate, the Ted Reeve School has also recruited and earned support from area businesses. “In recent years, we have been honoured to be recognized by our local Business Improvement Area,” said Casey. Business Improvement Areas in Toronto are consortiums of neighborhood businesses working in concert with the Toronto City Council to improve neighborhood safety and aesthetics, to attract new consumers and business tenants alike. “We have received sponsorships to assist with the costs of the School and to help keep our Program as financially accessible as possible,” he wrote.

Because of equipment costs, and the lessons novice players must take to learn fundamental skills like skating, stick handling, puck handling, and ice hockey, even at the youth level, can be a very expensive endeavor.

“That’s Rich in Tom’s old jersey from Sweden,” she said, referring to the photo above. “We couldn’t afford new equipment, but we put our boys in hockey because it would keep them healthy, and if they liked it, or got an education out of it, that was a bonus.” And get an education out of hockey, the Clune boys did. Rich, Matt, and Ben all attended St. Michael’s College School in Toronto, a small, private Catholic high school—their father Tom’s alma mater.

“We have lived in the same small home for 24 years, that we have renovated to accommodate the boys growing, so we could send them to a private school from 7th to 12th grade,” she recounted. “Our kids had great coaches. If you didn’t get your homework done, you couldn’t come to practice. You can’t buy that,” she insisted.

Neither can one buy the sense of community that the Ted Reeve Arena fostered in the Clune family’s neighbourhood.

“We worked full time, and I traveled quite a bit for my job,” said Anne Marie, “so our socialization came from going to the rink for our sons’ games, and to fundraisers, and things like that. Our friends started to join when we started ‘Coach Clune’s hockey school’,” she continued. “The kids made all their friends playing in tournaments all around the city of Toronto.”

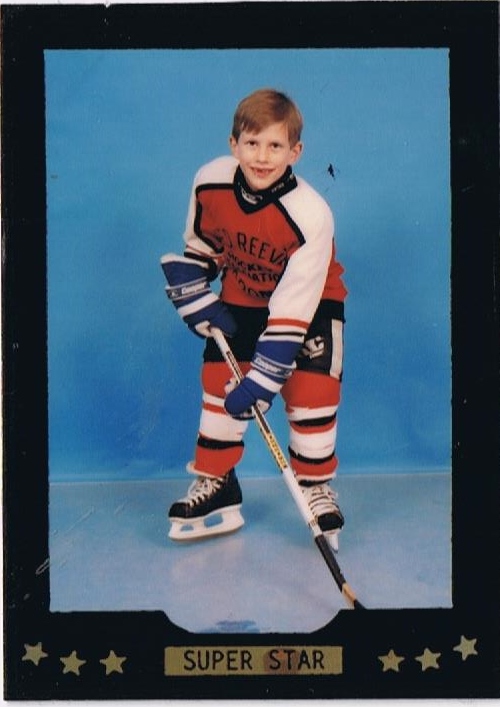

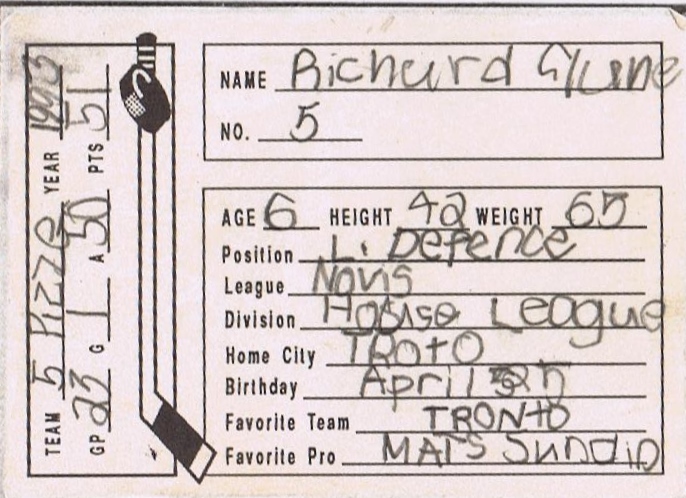

Back of Rich’s first hockey card

Home City: Troto

Favourite Team: Tronto

Favourite Pro: Mats Sundin

Goals: 1

Assists: 50

Her sons learned valuable life lessons from playing hockey, too, said Mrs. Clune. “Kids really like to help each other, and hockey really brings out the best in them in terms of teamwork,” she said. “They play the game with each other, and they begin to figure things out,” she continued, speaking about the impact of team sports on child development.

“The things Rich did earlier in his life,” said Anne Marie, referring to his House League play with his brothers and friends, “I believe helped him through his life challenges.” Rich Clune told OTF in an exclusive interview earlier this season that “If I’m patient and diligent, I usually get what I want, even if it comes to me a little differently than I planned it.” That attitude, asserts his mother, came from playing youth hockey, and learning, in a community rink with friends.

We asked Mrs. Clune to share any advice she might have for parents with no familiarity with hockey.

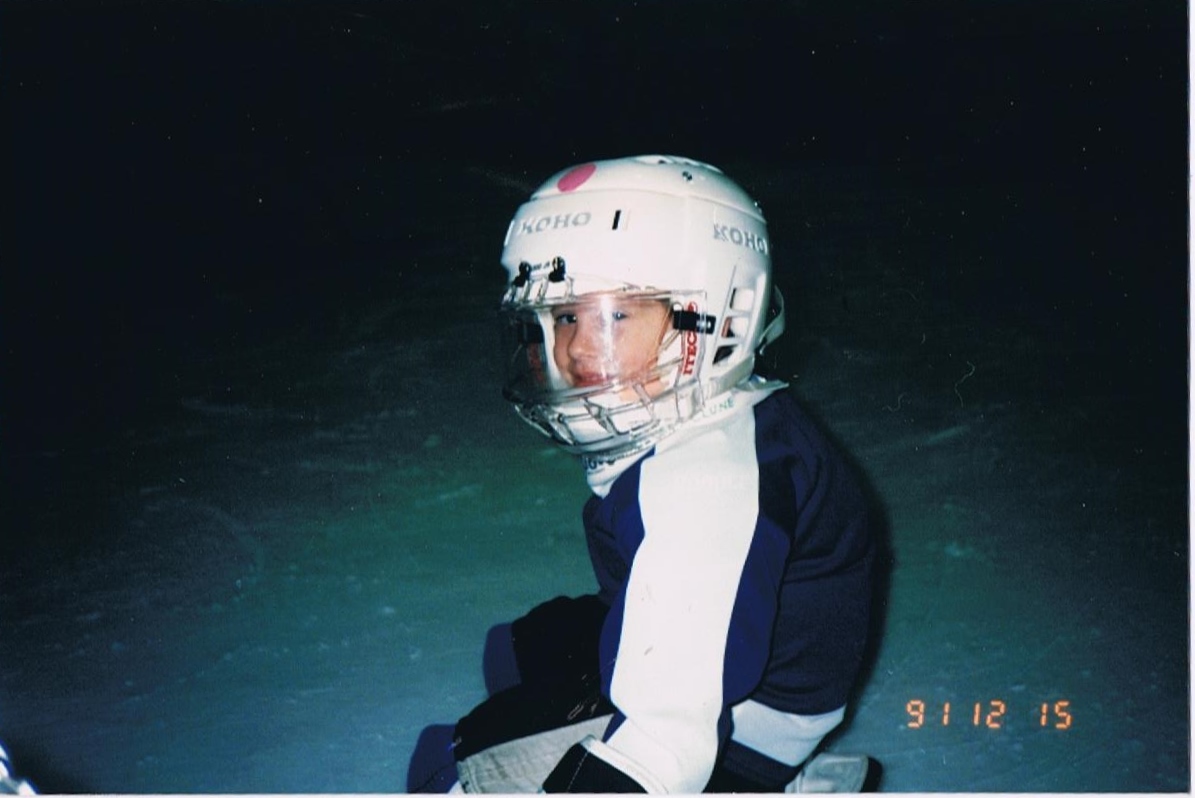

“I say to any parent now, ‘just let them be, let them have fun, and stay as far away from the coaches as you possibly can,'” she chuckled. Like teachers or school principals, coaches call parents when kids do something wrong, but they don’t pick up the phone every time a child connects a pass to a teammate, she said. “I never wanted to be one of those moms who was like, ‘play my kid, play my kid, play my kid,'” she related. “My boys used to say, ‘Mommy, stay away! And don’t scream,'” she laughed. “It’s not going to be for everyone,” she continued, “but I bet you Rich is still the last one out of the dressing room. He’s been the last frigging one out of the dressing room since he was five years old,” she said, suggesting that, while hockey may not be for everyone, the ones who grow to love the game are not easily separated from it.

Rich Clune showing off his Skate 2/Hockey-taught stick handling in an April 2013 game versus the Blue Jackets. Source: here.

“If I had it all to do all over again, I wouldn’t change a thing,” she said. “Just let your kids play, don’t go in the dressing room, let them have their own experiences, and become independent.”

Mrs. Clune does not mean that parents should abandon their children to strangers. When Rich first began to play competitively in Toronto at age 7, Anne Marie used to carry his equipment bag for him into the locker room, until Rich’s coach stopped her one day.

“If Rich is old enough to play competitive,” she remembers the coach saying, “then he is old enough to carry his own bag.” Anne Marie remembers, “Rich did look at me, and [the coach and I] agreed he was fine,” she recalled. “[Rich] always knew I would not leave him with a stranger, but I was just outside the dressing room.” From that day forward, the Predators left wing would never again allow his mother to carry his equipment.

After that day, said Anne Marie, “Rich started to figure things out on his own,” and that, she believes, is the bigger lesson for parents.

See the whole article, and more from On the Forecheck here.